Русская

Версия

Life

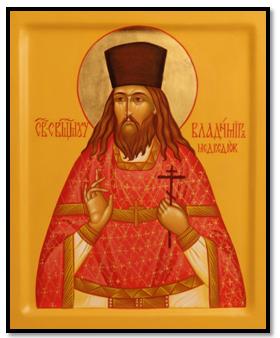

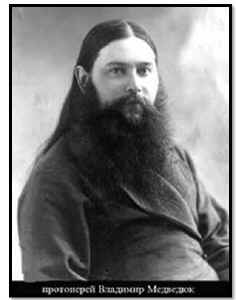

of Priest-Martyr

Vladimir (Medveduk)

Nov.

20/Dec. 5

Priest-martyr

Vladimir was born July 15th, 1888, in Poland, in the city

of Lukov of the Sedeletsk gubernia (province – A.K.*), in the

God-fearing family of a railroad worker, Faddey Medveduk. On his

deathbed, the father said to his son Vladimir: “My child, I yearn so

much for you to become a priest or at least a psalmist, as long as you

are a servant of Church.” The son responded that it was also his

wish.

Priest-martyr

Vladimir was born July 15th, 1888, in Poland, in the city

of Lukov of the Sedeletsk gubernia (province – A.K.*), in the

God-fearing family of a railroad worker, Faddey Medveduk. On his

deathbed, the father said to his son Vladimir: “My child, I yearn so

much for you to become a priest or at least a psalmist, as long as you

are a servant of Church.” The son responded that it was also his

wish.

Upon

graduating in 1910 from a seminary, Vladimir served as a psalmist in

Radomsk Cathedral in Poland. Peaceful life was interrupted by World

War I, and Vladimir Faddeevich, like thousands of others, became a

refugee. Upon his arrival to Moscow, he met Varvara Dmitrievna

Ivanukovich, who was descended from a deeply religious family in

Belarus and was also a refugee. In 1915 they married.

In

1916 Vladimir Faddeevich was ordained a deacon for the parish of

Martyr Irina on Vozdvizhenka in Moscow. There he served until 1919 and

then was ordained a priest for St. Savva parish on Tverskaya Street.

In 1921, he was appointed a rector of the parish of St. Mitrofan of

Voronezh in Petrovskiy Park in Moscow.

From

the very first days of his service in the church of St. Mitrofan,

Father Vladimir endeavored to organize and order the parish life. In

that ocean of passions, misfortunes, and suffering that was the Soviet

Russia of the time, his parish became for believers an island of love.

The young priest zealously carried out the duties of his ministry, and

immediately attracted religious youth, which he took pains to instruct

in the love of the Orthodox service and the Church. The church of St.

Mitrofan was often visited by choirs from other parishes attracting

many believers and lovers of church singing. So much so, that at times

the church could not contain all the visitors.

This

was the time of the New Church (a reformist, schismatic movement –

A.K.) debauchery, when with the help of the godless authorities, the

schismatics seized Orthodox churches with impunity. To avoid such a

lawless seizure, Father Vladimir locked the church himself after every

Divine Service and took the keys home with him. Seeing that they

cannot seize the church without the priest’s acquiescence, revivers

invited Father Vladimir to the reviver’s Bishop Antonin (Granovsky).

Demanding the keys from the church of the priest, he hollered:

Give

me the keys!

No,

Vladyka, I won’t! – Responded Father Vladimir.

I’ll

kill you! I’ll kill you like a dog!

Kill

me, – responded the priest. – We will stand together in front of

the Divine Throne.

That’s

how you are! – said Bishop Antonin, ceasing his demands. And so, the

revivers failed to take over the church.

In

1923, Father Vladimir was awarded a camilavka. In 1925, authorities

arrested the priest and, wielding spurious accusations, threatened him

with imprisonment in a concentration camp. The only way to regain his

freedom, they insisted, was through cooperation with the OGPU (the

[secret] police – A.K.). Father Vladimir agreed and was consequently

freed. For a while, the OGPU gave him some sort of tasks, usually

having to do with the Place-Keeper Metropolitan Petr, which he

fulfilled. As more time passed, however, the more discord he felt with

his conscience and the more tormented he was by his situation. Neither

his zealous service in church, nor his conscientious service of his

flock, could quiet this burning spiritual pain. Finally, Father

Vladimir decided to end his relations with the OGPU as their secret

agent, and confessed the sin of betrayal to his father-confessor. On

December 9th 1929 an OGPU detective summoned him with a

subpoena to one of the offices on Bolshaya Lubyanka (OGPU headquarters

– A.K.) and demanded an explanation. Father Vladimir stated to him

that he refused to cooperate any further. The next three days were

spent trying to talk him into changing his decision, but Father

Vladimir steadfastly refused, declaring that it was no use, because he

had already told it all to a priest in confession. On December 11th,

an order for his arrest was signed, and he was charged with

“divulging… information that was not to be disclosed.” On the 3rd

of February, 1930, the Board of OGPU sentenced him to three years in a

concentration camp, which he served on the construction of the

Belomorsko-Baltiyskiy canal.

In

1923, Father Vladimir was awarded a camilavka. In 1925, authorities

arrested the priest and, wielding spurious accusations, threatened him

with imprisonment in a concentration camp. The only way to regain his

freedom, they insisted, was through cooperation with the OGPU (the

[secret] police – A.K.). Father Vladimir agreed and was consequently

freed. For a while, the OGPU gave him some sort of tasks, usually

having to do with the Place-Keeper Metropolitan Petr, which he

fulfilled. As more time passed, however, the more discord he felt with

his conscience and the more tormented he was by his situation. Neither

his zealous service in church, nor his conscientious service of his

flock, could quiet this burning spiritual pain. Finally, Father

Vladimir decided to end his relations with the OGPU as their secret

agent, and confessed the sin of betrayal to his father-confessor. On

December 9th 1929 an OGPU detective summoned him with a

subpoena to one of the offices on Bolshaya Lubyanka (OGPU headquarters

– A.K.) and demanded an explanation. Father Vladimir stated to him

that he refused to cooperate any further. The next three days were

spent trying to talk him into changing his decision, but Father

Vladimir steadfastly refused, declaring that it was no use, because he

had already told it all to a priest in confession. On December 11th,

an order for his arrest was signed, and he was charged with

“divulging… information that was not to be disclosed.” On the 3rd

of February, 1930, the Board of OGPU sentenced him to three years in a

concentration camp, which he served on the construction of the

Belomorsko-Baltiyskiy canal.

Meanwhile,

his family was evicted from the church property and became homeless.

That was what the clergyman had feared most of all. While

incarcerated, he began to ardently pray to holy St. Sergius and his

parents, schema-monk Cyril and schema-nun Maria, that by their prayers

his family could find themselves a shelter. And it was in Sergiev

Posad (St. Sergius monastery – A.K.) that they found themselves a

sanctuary. At first they were aided in this by Olga Serafimovna

Defendova, a well-known benefactress, who in the 1920’s served the

sick Metropolitan Makariy (Nevsky) in Nicolo-Ugreshskiy monastery.

In

1930, on the Holy Day of the Elevation of the Cross of the Lord,

Father Vladimir’s son Nikolay entered Elijah Church in Sergiev Posad.

When he approached for the anointing, the rector of the church, Father

Alexander Maslov, said to him:

This

is the first time, young man, that I see you in our church.

We,

batyushka, are in big trouble, – said Nikolay. – There are five of

us left; my father’s been taken. So mother and Olga Serafimovna have

been looking for shelter for two days throughout the city. As soon

they find out that there are five children, no one wants to rent to

us. We don’t know what to do.

Father

Alexander called over one of the women parishioners and said to her:

Nadezhda

Nikolayevna, you yourself are in great affliction, so you should

understand and receive this family.

Father,

bless. – She responded.

That

is how they ended up with the Aristov family. A few months before

this, the head of the household, a deacon of the Ascension Church, had

been arrested and executed by a firing squad. His home became a safe

harbor for Father Vladimir’s family for many years to come. After

finishing his time in 1932, Father Vladimir lived here with his family

and traveled to Moscow to serve in the parish of St. Mitrofan. In

1933, the church was closed by the authorities, and Father Vladimir

received a place in Trinity Church, in the village of Yazvische of the

Volokolamsk region.

In

1935, Father was elevated to the rank of archpriest. In Yazvische,

Father Vladimir was given a small church guardhouse with only two

windows, which is where the whole family moved in. Living there was

crowded, but the parish had no other quarters. One day, a neighbor

from across the street came to them and said: “Father Vladimir, I

offer you my home. Live for as long as you want, I don’t need a

kopeck from you.” For the next ten years, the family of Archpriest

Vladimir lived in the house of this benefactor.

At

that time, there were many in the Volokolamsk region that had returned

from internal exile and were prohibited from living in Moscow. Among

them, there was Archdeacon Nikolay Tzvetkov, who was admired by

believers for his ascetic life and prescience. Archpriest Vladimir

often visited him for the resolution of difficult issues. Once,

Archdeacon Nikolay asked him to serve at night in his house. The

windows were tightly covered with curtains. They put on their

vestments; there were just a few parishioners. Suddenly, during the

service, someone knocked on the window. The memories of the jail and

the camp were still fresh, and Father Vladimir began to take off his

vestments. “Father Vladimir, do not lose heart; stay as you were.

We’ll soon find out.” – Said Father Nikolai. As it turned out,

it was just a passerby, who wanted to find out how to get to the

station.

The

last time Father Vladimir came to Archdeacon Nikolay was in the spring

on 1937 to congratulate him on his saint’s day. But the Archdeacon

did not even come out, only said from behind the door: “Christ is

Risen!” That was all. Father Vladimir grew very upset and asked the

woman servant (poslushnitza – one who is in spiritual obedience. -

A.K.) of the godly man to tell him, that this is Father Vladimir from

Yazvische to congratulate him on his saint’s day. She did as told;

Father Archdeacon repeated to her: “Say to him: Truly He is

Risen!” Father Vladimir was very upset, because he realized that

this was said by the prescient elder as a sign that they would not

meet again in this life.

In

the summer of 1937, mass arrests began. In November, Archpriest

Vladimir visited Moscow and said upon returning that he was sure he

would soon be arrested. “It is not the exile and death that I

fear,” he said. “I fear the journey there; when they drive the

prisoners tens of kilometers a day; and the guards finish off those

who fall down with the stocks of their rifles; and then wild animals

come out to devour their dead bodies.”

In

the summer of 1937, mass arrests began. In November, Archpriest

Vladimir visited Moscow and said upon returning that he was sure he

would soon be arrested. “It is not the exile and death that I

fear,” he said. “I fear the journey there; when they drive the

prisoners tens of kilometers a day; and the guards finish off those

who fall down with the stocks of their rifles; and then wild animals

come out to devour their dead bodies.”

On

November 11th of 1937, a report came in the Volokolamsk

NKVD (predecessor to the KGB – A.K.) stating that there was a

meeting held in the village of Yazvische, which had almost no youth

attending. Allegedly, Nikolai, the son of Archpriest Vladimir, held an

alternate meeting not far from the reading house, where the sanctioned

meeting was taking place; and all the youth joined him. The report

also stated that the priest was being visited daily by as many as

twenty people, mostly old men and women from various kolkhozes

(collective work settlements – G.L.) of the Volokolamsk and

Novopetrovsk regions. On November 24th of 1937, an arrest

order was issued for the priest.

On

the eve of November 25th, Father Vladimir, who was going to

serve a funeral liturgy the next day, was standing by the window in

his room reading the priest’s prayer rule. Besides the priest’s

family, there were two monastic novices in the house, Maria Briantzeva

and Tatiana Fomicheva, who after the forced closing of their monastery

lived at Trinity Church performing the duties of the psalmist and the

altar cleaner. That evening, they were helping the priest’s spouse

to cut cabbage. Suddenly, Father Vladimir saw the president of the

village Soviet and a militiaman walking past his window. “I think

they are coming for me,” said Father Vladimir to his daughter. A few

minutes later they were already in the house. “Let’s go to the

village Soviet, we need to clarify something,” said one of them.

Father Vladimir began to say good bye to everyone, while the NKVD man

purposely hurried him, saying that he would be back soon. Father

Vladimir knew, though, that he would not return. So, he blessed

everyone and said to his daughter: “It is doubtful, my little one,

that we will see each other again.” Along with him, novices Tatiana

and Maria were also arrested.

On

the same day, the priest’s spouse, Varvara Dmitrievna, put together

a package and brought it to the village Soviet, but was not allowed to

visit her husband, and was told instead that in the evening they would

come to search the house. Late at night, the same NKVD man came back

and with a furious uproar began to conduct the search. The shelves

creaked, the books fell. The search came down to him taking some

random items and throwing them, without a record, in some bags.

Interrogations

began immediately after the arrest. First, on November 26th,

the president and the secretary of the village Soviet, as well as the

“witnesses du jour,” were called in and signed sworn testimony

that had been prepared by the detective. On the same day, Archpriest

Vladimir was interrogated.

“The

inquest has evidence,” declared the detective, “That your quarters

are often visited by nuns and believers from nearby settlements of the

Volokolamsk and Novopetrovsk regions. Give your testimony on that

issue.”

“Fomicheva

and Briantzeva have visited my quarters, but very infrequently.

Believers visit my quarters only with religious needs.”

“The

inquest is aware that there have been meetings in your quarters. In

these meetings, you discuss the policies of the Party and the

Soviets.”

“There’ve

never been any meetings at my quarters.”

“The

inquest has evidence that you conduct counterrevolutionary and

anti-Soviet agitation with various persons in your acquaintance.”

“I

have never engaged in counterrevolutionary and anti-Soviet

agitation.”

“Your

testimony is false. In connection with your case, a number of

witnesses have been interrogated who confirm you conducted

counter-revolutionary and anti-Soviet agitation. The inquest demands

truthful testimony.”

“I

declare again, that I have never conducted counterrevolutionary and

anti-Soviet agitation.”

Novices

Mariya Briantzeva and Tatiana Fomicheva were interrogated on the same

day.

Novice

Maria Briantzeva was born in 1895 in the village of Severovo of the

Podolsk region of the Moscow province in the family of a peasant

Grigoriy Briantzev. The farm was not a big one – a house with

attachments, two sheds, a barn, a horse, and a cow. In 1915, when the

girl turned twenty, she joined a monastery as a novice. After the

revolution, she continued in the Boris-and-Gleb monastery in the

Voskresensk region until its closure in 1928. That same year, she

returned to her native Podolsk region.

Novice

Maria Briantzeva was born in 1895 in the village of Severovo of the

Podolsk region of the Moscow province in the family of a peasant

Grigoriy Briantzev. The farm was not a big one – a house with

attachments, two sheds, a barn, a horse, and a cow. In 1915, when the

girl turned twenty, she joined a monastery as a novice. After the

revolution, she continued in the Boris-and-Gleb monastery in the

Voskresensk region until its closure in 1928. That same year, she

returned to her native Podolsk region.

Novice

Tatiana was born in 1897 in the village Nadovrazhnoe, not far from the

town of Istra of the Moscow province, in the family of a peasant

Alexey Fomichev. In 1916, she joined a monastery as a novice and after

the revolution continued her obedience in the Boris-and-Gleb

monastery. In 1928, the authorities closed the monastery, and she

moved back with her parents to Nadovrazhnoe.

In

1931, the authorities began to persecute the monks and nuns of the

closed-down monasteries. Many of them, despite the convents’

closures, endeavored to hold on to the monastic order in their lives.

Some settled near their convents, earning their keep like the ascetics

of old with their handiwork, and attended the services of the nearest

parish churches. That is how, early in 1931, the OGPU had created a

“case” against the nuns of the monastery of the Elevation of the

Cross situated near the village of Lukino of the Podolsk region.

Before the Revolution, there were about a hundred nuns endeavoring in

the monastery of the Elevation of the Cross. After the Revolution, the

monastery was closed down, but the nuns managed to obtain a permit to

open in the walls of the convent a farm cooperative, which consisted

of the former monastic sisters. In this way monastic life had

continued here until 1926, when the monastery was definitively

abolished, and a workers’ resort named Karpov was housed in its

walls. Even then, twelve of the convent’s sisters did not leave,

some of them working for the resort, and some settling in the nearby

villages and earning a living with their handiwork. To pray, everyone

went to St. Elijah Church in Lemeshevo. The church choir also

consisted of the nuns and novices of the closed-down mona-steries.

Novices Maria Briantzeva and Tatiana Fomicheva sang in that choir.

On

May 13th 1931, the general manager of the resort testified

to the detective of the OGPU that “in the former monastery, where

the workers resort is now located, there are still bells on the belfry

and icons on the walls, as well as various church adornments, and

behind the fence there still stands a church. It is difficult to

explain why, to this day, the bells are not taken down, and the

monastery is not overhauled to give it a normal appearance. However,

the presence, to this day, of the twelve nuns, and their anti-Soviet

activity, gives reason to surmise that under their influence, the

backward population of the surrounding villages did not support the

taking down of the bells. The twelve nuns constitute none other than a

parish around the former monastery … these twelve nuns have

communication between each other; take residence near the monastery;

are connected with the kulak element; often mix among peasants

agitating them against measures taken by the Soviet authorities; have

intercourse with the resort visitors, using all means to influence

them, acting as though they’ve been cheated by the Soviet

authorities.”

The

resort’s culture director testified: “I will express my own

opinion concerning the ‘holy’ nest around the church, even though

I have only stumbled onto this nidus two or three times, and only very

superficially at that, while surveying the locality, the cemetery, and

the church. Nonetheless, I clearly perceived it as precisely that, a

nest and a hotbed, hostile to us, with its ominous old women cursing

our system. It is noteworthy how strong their influence is. Peasant

girls, not yet twenty five years of age, with whom I conversed near

the church, believe in God. When I tried to correct their minds, they

listened at first, but soon cut me off and went in to the church led

by the old nuns. During winter, instances were noted when the resort

visitors also went to church. Which is why, in my opinion, this nexus

of infection should altogether be liquidated, up to and including the

demolition of the church.”

On

May 18th, 1931, novices Maria and Tatiana were arrested and

confined in Butyrskaya prison in Moscow. All in all, seventeen nuns

and novices from various convents, who had settled near the

closed-down Elevation of the Cross monastery, were arrested at that

time.

On

May 18th, 1931, novices Maria and Tatiana were arrested and

confined in Butyrskaya prison in Moscow. All in all, seventeen nuns

and novices from various convents, who had settled near the

closed-down Elevation of the Cross monastery, were arrested at that

time.

The

landlord of the house in Lemeshevo, where novice Tatiana lived,

testified that the novice does handiwork, which she sells to the

peasants of the neighboring villages, and that she is predisposed

against measures taken by the Soviet authorities. One of the false

witnesses testified that novice Tatiana was a zealous church person

and conducts active anti-Soviet activity. Another witness testified

that novice Maria had said to the peasants: “What do you need

kolkhozes for, and why should you join them, when in them violence is

being perpetrated against peasants? These days you, peasants, are

corralled in such a sty, where there are no laws prescribed.” And

the peasants supposedly hollered in response to the words of one of

the novices: “Matushkas are right, after all, they do know more than

us.”

During

interrogation, novice Maria said: “Towards the Soviet authorities I

feel nothing but disdain. The Soviets have strangled us. Communists

have instituted persecution of the Church, closing down churches and

demanding high taxes. As concerns the anti-Soviet agitation, I am not

guilty.”

On

May 29th, 1931, the OGPU tribunal convicted novices Maria

and Tatiana to five years of hard labor. Upon their release in 1934,

Maria settled in the village of Vysokogo, and Tatiana in the village

of Sheludkovo of the Volokolamsk region, and started assisting

Archpriest Vladimir in Trinity church. They were arrested in 1937

together with him.

During

their interrogation on November 26th, 1937, the novices

categorically refused to confirm the accusations made up by the

detectives, and refused to testify against anyone else. On November 28th,

the inquest was concluded, and the next day, the NKVD tribunal

sentenced Archpriest Vladimir to execution by firing squad, and

novices Tatiana and Maria to ten years of hard labor.

Meanwhile,

the wife of Father Vladimir, Varvara Dmitrievna, was notified that the

prisoners were being prepared to be sent to Moscow, and that the train

would pass the station closest to their village at 3:00 pm. She was

told that the prisoners would be transported in the first car, which

would be barred. Varvara Dmitrievna, with the children, came to the

train with provisions she wanted to give to her husband. The train

stopped, but the car with the prisoners was surrounded by guards, who

would not let anyone approach it. The family strained to search into

the barred windows and suddenly noticed that in one of them, there

appeared a hand and blessed them with a priest’s blessing. The train

remained at the station for three minutes, which to them seemed like

one moment. After the train’s departure, they were too exhausted to

walk back the three kilometers back home, while carrying things

intended for Father Vladimir. Just then, a teenager from Yazvische

came up to them and asked what had happened. They explained, and he

helped to carry everything back to their home.

Archpriest

Vladimir Medveduk was executed by firing squad on December 3rd,

1937, and buried in an unmarked mass grave in Butovo, near Moscow. He

was adjoined to the community of saints New Martyrs and Confessors of

Russia, for Church-wide commemoration, at the Jubilee Archbishop Sobor

of the Russian Orthodox Church in August of 2000.

Novice

Maria Briantzeva returned home after serving her sentence, and Novice

Tatiana Fomicheva accepted death while incarcerated.

Igumen

Damaskin (Orlovsky). “Martyrs, Confessors and Heroes of Devotion

of the Russian Orthodox Church in the XX Century”.

Tver,

Publishing House “Bulat”, volume 1, 1992; volume 2, 1996; volume

3, 1999; volume 4, 2000; volume 5, 2001.

Translated

by Anna Katsnelson.

Media

Office of the Eastern American Diocese