November 20, 2013

"Father Victor’s Washington:" An Article on the Life of our Priest

in the Capital

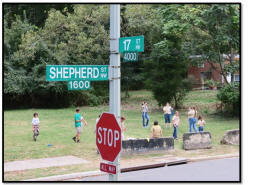

Russian

speech is heard on Shepherd Street (or "Pastor Street," if you

will), coming from the third generation of Russian scouts, who are

playing volleyball across the street from a church. Playing at some

distance from their teachers, this younger generation switched to

English from time to time. At the church, under a tent, is a group

of younger children, who repeated the words of "Our Father" uttered

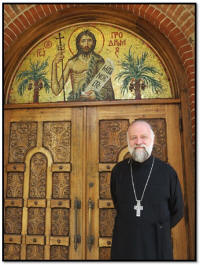

by one of the girls. I stood at one side and marveled at the mosaic

shining in the sunlight, the tile-work of the church rising to the

sky… Then slowly, through the Indian-summer fog of sunny orange

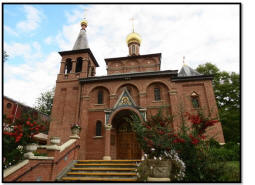

bushes and rich colors, I ascended the steep staircase. St. John the

Baptist Cathedral in America’s capital was built in the

Muscovite-Yaroslavl style of the 17th century, like a carved

statuette sitting in the palm of one’s hand. There is only a handful

of such churches in Orthodox America. And parish churches dedicated

to the Beheading of Righteous John the Forerunner, they say, number

only some 25 throughout the Orthodox world.

Russian

speech is heard on Shepherd Street (or "Pastor Street," if you

will), coming from the third generation of Russian scouts, who are

playing volleyball across the street from a church. Playing at some

distance from their teachers, this younger generation switched to

English from time to time. At the church, under a tent, is a group

of younger children, who repeated the words of "Our Father" uttered

by one of the girls. I stood at one side and marveled at the mosaic

shining in the sunlight, the tile-work of the church rising to the

sky… Then slowly, through the Indian-summer fog of sunny orange

bushes and rich colors, I ascended the steep staircase. St. John the

Baptist Cathedral in America’s capital was built in the

Muscovite-Yaroslavl style of the 17th century, like a carved

statuette sitting in the palm of one’s hand. There is only a handful

of such churches in Orthodox America. And parish churches dedicated

to the Beheading of Righteous John the Forerunner, they say, number

only some 25 throughout the Orthodox world.

How is it that a church, devoted to such a sad event, came to be in

this intellectual, refined city of Washington?

The founding of this church was tied to an important event in the

life of the Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia and the

Russian Diaspora. In 1949, Archbishop John (Maximovitch) came to the

American capital from the distant island of Tubabao, with the aim of

interceding for his flock, which was forced to flee communist China

and found refuge on that small Pacific island. Five thousand

Russians were all that the Philippine government agreed to take in,

putting them on an island that was hit by typhoons every year. St.

John remained with his flock for three years, as the Russians lived

in jungle camps, serving in a tent chapel, walking about the entire

island in prayer every day. And over the entire period, not one

storm hit the island! In 1949, the holy man came to the American

capital to plead with U.S. senators to change their immigration

quota. As a result, legislation was passed which allowed these 5,000

Russians to come to America as permanent residents. While in

Washington, St. John founded the first parish of the Russian Church

Abroad in the city. He set down two conditions: that on that very

day they would perform an All-Night Vigil in his apartment and

Liturgy the next day, and dedicate the community to that day’s

feast: the Beheading of St. John the Forerunner.

This was the only parish founded by St. John of Shanghai in the

United States. Inside the church, on the left side of the ambo, is

an image of the saint, depicting the Capitol Building in which

Archbishop John pleaded on behalf of his flock, along with other

miraculous events connected to his life. In 1983, parish rector

Archpriest Victor Potapov, on a pilgrimage to the Holy Land, went to

St. George of Koziba Monastery in the Judean desert. The monastery

has a large part of the skull of St. John the Baptist. Learning

where the pilgrims were from, the abbot gave his blessing for a part

of the relic to be given to the parish, now one of 850 other relics

in the cathedral.

Fr. Victor has served at the cathedral for 37 years. In the Church

Abroad, most priests are forced to also hold "civil" jobs as they

minister to their flock, since most parishes cannot provide full

financial support to their priests. Fr. Victor took a job at Voice

of America radio station after he became convinced that St. John the

Baptist Cathedral needed a second priest. His family had made its

way to the American continent from the German camp of Manchenhof,

where Fr. Victor was born in 1948. His father, an officer in

Vlasov’s liberation army, had to change his name, so they became the

Potapovs.

"Papa and the other Vlasov soldiers were taken prisoner," said Fr.

Victor. "After the war they were repatriated to the Soviet Union.

The next day after the betrayal, they were going to execute him. But

that night he had a dream. A voice told him ‘Run, run!’ And so he

fled the transit camp. After 30 days of wandering through the

forests and towns of Germany, he made his way to a DP

[displaced-persons] camp, where he met my mother, whose family had

been deported to Germany as forced laborers, and they married.

Archpriest Mitrofan Znosko-Borovsky married them in the barracks

chapel; he was later to become a bishop of ROCOR.

"In 1951, we came to New York. My grandfather, searching for work,

headed to Cleveland, and soon brought the rest of the family there.

Papa became a builder, and built 3-4 houses a year, which supported

us. In fact, he also built our St Sergius Cathedral in Cleveland."

"I Was Forced to Go to Church Under Threat of the Rod"

"I

grew up during the Cold War and very much wanted to assimilate to

the American way of life," continued Fr. Victor. "Americans did not

discern between Russians and Soviets. We tried to explain that

Russians were the first victims of the godless communist regime, but

all Russians were immediately deemed to be communists. This was very

unpleasant, and I tried to quickly ‘melt in the American pot.’

"I

grew up during the Cold War and very much wanted to assimilate to

the American way of life," continued Fr. Victor. "Americans did not

discern between Russians and Soviets. We tried to explain that

Russians were the first victims of the godless communist regime, but

all Russians were immediately deemed to be communists. This was very

unpleasant, and I tried to quickly ‘melt in the American pot.’

"I was forced to go to church under threat of the rod, because we

had to accompany my grandmother to church, which was in a bad

neighborhood. Once when I was 14, I went to church with my

grandmother; there were almost no other parishioners in church that

day. Fr. Michael Smirnov was serving, and in one instant, by Divine

mercy, it occurred to me that everything around me had profound

meaning. From then on I began to immerse myself in Orthodox

Christianity. Fr. Michael invited me to become an altar boy; he

taught me to read Church Slavonic. I was a rascal as an adolescent,

but thanks to Church reading, I was able to overcome this fault.

"In the 1960’s, I began to travel to the monastery in Jordanville.

They had a wonderful program then: the ‘summer boys.’ Participants

served as young novices; in the morning we would attend church,

serve in the altar, and whoever could would sing on the kliros. We

were taught the Law of God, we talked to the monks who had come

there from various monasteries of Russia and passed on wonderful

monastic traditions to us.

"After I graduated, I enrolled in Holy Trinity Seminary in

Jordanville, NY, and studied together with our present First

Hierarch, Metropolitan Hilarion, who was then just Igor Kapral. For

the first few months we lived in the same dorm room. The future

Vladyka was a good student, he loved to read the Lives of Saints,

and often read about how martyrs suffered aloud, with tears in his

eyes."

"I Met my Matushka at the Holy Sepulcher of the Lord"

"It

was the summer of 1970. I went to Jerusalem with a group of pilgrims

headed by Bishop Laurus, the future metropolitan, and before that I

had gone to Mt. Athos and even considered taking the monastic path.

In Jerusalem, one pilgrim who was dismayed at my thoughts of

monasticism said that she noticed a perfect girl for me, Masha

Tchertkoff from Paris, the daughter of Archpriest Sergei Tchertkoff,

who served as a protodeacon under Bishop John (Maximovitch) for ten

years, when he was the Archbishop of Brussels & Western Europe.

Masha was on a pilgrimage of Russian Orthodox youth from Paris.

"It

was the summer of 1970. I went to Jerusalem with a group of pilgrims

headed by Bishop Laurus, the future metropolitan, and before that I

had gone to Mt. Athos and even considered taking the monastic path.

In Jerusalem, one pilgrim who was dismayed at my thoughts of

monasticism said that she noticed a perfect girl for me, Masha

Tchertkoff from Paris, the daughter of Archpriest Sergei Tchertkoff,

who served as a protodeacon under Bishop John (Maximovitch) for ten

years, when he was the Archbishop of Brussels & Western Europe.

Masha was on a pilgrimage of Russian Orthodox youth from Paris.

"I did not really want to introduce myself, but out of propriety,

not wishing to disappoint her, I did. I spoke no French, Masha did

not speak English well, so we spoke Russian. Four days later, she

left for France, and I returned to America. We began to write, and

one year later, at the end of August 1971, we were married in

Cleveland. Her father, Fr. Sergei, performed the ceremony with her

uncle, Fr. Vladimir Rodzianko, future Bishop Vasily of the Orthodox

Church in America. On January 1, Metropolitan Philaret (Voznesensky)

ordained me to the diaconate, and sent me to the renowned Holy

Virgin Protection Church in Nyack, NY. The famous author of the Law

of God, Archpriest Seraphim Slobodskoy, had served at this parish

for many years. Serving in Nyack as a deacon was very rewarding. We

had a magnificent parish school, where I taught the Law of God and

eventually, with Elena Slobodskoy and Sophia Koulomzin, began the

20-year run of the Orthodox journal ‘Trezvon.’ Our first son,

Matthew, was born in Nyack; he only lived for seven days. We managed

to baptize him in time, and even gave him Holy Communion. Matthew,

through his short life and death, taught us young parents a great

deal about life, and this helped in our further ministry…

"Once we went with Archbishop Nikon (Rklitsky) to attend the feast

day celebrations of St. Panteleimon Church in Hartford, CT. On the

way, we drove by the town of Stratford. Vladyka said that they were

in need of a priest for the new Church of the Presentation of Christ

in the Temple. I told Vladyka that I was prepared to take on that

assignment. On September 1, 1974, Metropolitan Philaret ordained me

to the priesthood, and I was assigned to that parish. It was small,

and we lived on the church grounds. It provided good experience in

the priesthood, but the parish could not support me. I needed to

find other work, and I was able to find a job at Bedford

Publications in New York City."

"How I Helped Immigrants"

"The

publishing firm existed on government subsidies, printing and

distributing Russian-language literature which was banned in the

USSR: George Orwell’s 1984,

the works of Solzhenitsyn, samizdat manuscripts and political

literature, and found ways of delivering it to the Soviet Union. I

was hired to conduct interviews with recent immigrants. These were

the standard type: ‘What radio stations did you listen to, what kind

of literature interests you?’… I helped the newly arrived immigrants

find a place to live, rented moving vans, helped them in their daily

needs.

"The

publishing firm existed on government subsidies, printing and

distributing Russian-language literature which was banned in the

USSR: George Orwell’s 1984,

the works of Solzhenitsyn, samizdat manuscripts and political

literature, and found ways of delivering it to the Soviet Union. I

was hired to conduct interviews with recent immigrants. These were

the standard type: ‘What radio stations did you listen to, what kind

of literature interests you?’… I helped the newly arrived immigrants

find a place to live, rented moving vans, helped them in their daily

needs.

"During these interviews, it turned out that religion played an

important role in their lives. Many of them had listened to BBC

broadcasts of Metropolitan Anthony (Bloom), Fr. Vladimir Rodzianko

(later Bishop Vasily), Bishop John (Shakhovskoy), and Fr. Alexander

Schmemann; they desperately desired to own a Bible, and

philosophical and religious literature. Then I suggested to my

superiors that they send religious publications to the USSR. They

received the idea well, and I was charged with buying books and

sending packages. I would buy the works of Bulgakov, Frank,

Berdyaev, Solzhenitsyn, material published by Holy Trinity Monastery

in Jordanville, and found sailors, professors, and delegates who

came for ecumenical meetings, who enthusiastically took these

publications home.

"My commute from Connecticut to New York lasted for three years. It

would take three hours; on the way I would read, perfect my Russian,

and converse with interesting people. It was fascinating work, but

then a recession hit. My bosses decided that as a priest who

receives pay from my church, I could be laid off. But I could no

longer imagine my life separated from Russia, and began sending my

résumé to large firms which had any kinds of relationship with

Russia, offering my services as a translator or consultant."

"How St. John Helped Me"

"It

was 1976," remembers Fr. Victor. "I knew that in a few months I will

be jobless. One evening my matushka and I were at home after Vigil,

and she asked me: ‘Do you regret becoming a priest?’ ‘Of course

not,’ I replied. ‘When I stand before the altar table and perform

the Bloodless Sacrifice, this gives me such strength, such joy, that

I am prepared to face anything.’ She was satisfied with that answer.

That night as I slept, Vladyka John of Shanghai appeared to me in a

dream. I had never known him personally, but revered him. And

although I am skeptical about the significance of dreams, I still

remember how that night Vladyka John talked to me for a long time,

and asked me the same question as my matushka: ‘Do you regret

becoming a priest?’ Again, I answered that I did not, at all.

Vladyka then answered that he also did not regret that I became a

priest, and discussed with me something about some important work to

be done relating to Russia. I don’t remember exactly what Vladyka

told me, but he planted within me a sense of confidence in the

future. I did not tell my matushka about this at the time. I found

myself in some sort of peaceful bliss, and I had to make sense of

what I experienced...

"It

was 1976," remembers Fr. Victor. "I knew that in a few months I will

be jobless. One evening my matushka and I were at home after Vigil,

and she asked me: ‘Do you regret becoming a priest?’ ‘Of course

not,’ I replied. ‘When I stand before the altar table and perform

the Bloodless Sacrifice, this gives me such strength, such joy, that

I am prepared to face anything.’ She was satisfied with that answer.

That night as I slept, Vladyka John of Shanghai appeared to me in a

dream. I had never known him personally, but revered him. And

although I am skeptical about the significance of dreams, I still

remember how that night Vladyka John talked to me for a long time,

and asked me the same question as my matushka: ‘Do you regret

becoming a priest?’ Again, I answered that I did not, at all.

Vladyka then answered that he also did not regret that I became a

priest, and discussed with me something about some important work to

be done relating to Russia. I don’t remember exactly what Vladyka

told me, but he planted within me a sense of confidence in the

future. I did not tell my matushka about this at the time. I found

myself in some sort of peaceful bliss, and I had to make sense of

what I experienced...

"I sent a letter to Voice of America radio station and offered my

services. A few days later, they invited me to New York for an

interview. I went, and soon Nikita Moravsky called me; he was one of

the people Vladyka John had rescued from Tubabao. He was the

director of the Soviet Program of Voice of America, the number-one

man there, having earlier worked as the cultural attaché at the

American Embassy in Moscow. When I began to work there, this

remarkable person was preparing to retire. He summoned me and said

‘You’re hired.’ Nikita Valerianovich and I then became close

friends; he joined our Committee for the Defense of Persecuted

Orthodox Christians, and became a parishioner of our cathedral. A

year or so ago, I performed his funeral…

"After Voice of America made me an offer of employment, I went to

see Metropolitan Philaret. He gave me his blessing to move to the

Washington parish, where the rector for 27 years had been the Greek

Archimandrite Nicholas (Pekatoros). Fr. Nicholas had an interesting

life. He was born in the end of the 19th century in Odessa to a

family of Greek Russians. He was ordained to the priesthood under

Patriarch Tikhon in 1922 and, until 1929, served under Holy

Hieromartyr Bishop Onuphry (Gagaliuk) in the Kherson-Odessa Diocese

in the Ukraine. In 1929, Fr. Nicholas left for Greece, where he was

soon tonsured a monk. He served in the Church of the Most Holy

Trinity in Athens, attached to the Russian Embassy in Greece. In

1952, he moved to the USA and, from 1953 to 1980, was the senior

priest of the Washington cathedral.

"After I was hired by VOA, the question arose about what to do with

the Stratford parish. I promised to the parishioners of Presentation

Church that I would not leave until a replacement was found, and so

every weekend I would travel from Washington, DC to Stratford to

serve Vigil and Liturgy."

To the U.S. Capital

Four

and a half hours by car separate the U.S. capital from the ‘capital

of the world,’ New York City, but the cities and their inhabitants

are unbelievably different. Though Ilf and Petrov [early Soviet

humorists ‒ transl.] described Washington as "Single-Storied

America," both cities in my opinion are two different

"non-Americas."

Four

and a half hours by car separate the U.S. capital from the ‘capital

of the world,’ New York City, but the cities and their inhabitants

are unbelievably different. Though Ilf and Petrov [early Soviet

humorists ‒ transl.] described Washington as "Single-Storied

America," both cities in my opinion are two different

"non-Americas."

In October, the city is still in full bloom and there are no signs

of autumn. Only the Japanese cherry tree is not blossoming ‒ it is

the symbol of the National Cherry-Blossom Festival. That happens in

the springtime, when the whole city takes on a whitish-pink

coloration, and its residents and visitors are enchanted with the

Japanese blossoms.

Pierre-Charles L’Enfant, who laid out the plan for the city of

Washington, DC in the late 18th century, included diagonal avenues

which would be named for the states of the Union. These intersect

with streets which bear the names of generals, admirals, and famous

people, while others are numbered or named by letters of the

alphabet. Massachusetts Avenue was devoted to diplomats: this is

where most European embassies are located.

Washington, and especially its old town, Georgetown and Capitol

Hill, preserved the buildings of the 19th century. There are no

skyscrapers in the city: legislation prohibits any building rising

above the Capitol and the Washington Monument. Broad avenues,

severe, sharp-hewn and polished buildings also impart a sense of

grandeur and scale.

Geographically, the American capital is located within the state of

Maryland, but the Federal Government administratively separated the

city of Washington (not to be confused with Washington State on the

Pacific West Coast), into a separate unit ‒ the District of

Columbia. It forms its own capital, with its own budget, and

guaranteed municipal independence, which visitors can observe.

Without a penny in his pocket, a tourist can visit most of the

galleries and museums here, from the historic to the cosmic. You can

see the Capitol from almost all of them. But its proximity is an

illusion; one needs to reserve enough time after touring the museums

to reach the main legislative building in the nation: past the

monolithic government buildings, where Congressmen and Senators and

countless federal employees work… One does not sense under one’s

feet and under layers of asphalt the tunnels that provide access to

senators in bad weather (and to simply avoid emerging from their

office buildings) via train to the Capitol Building… You can walk

past the largest library in the world, the Library of Congress. Its

director, the scholar and admirer of Russia, James Billington,

received Sretensky Monastery Men’s Choir within its walls, and

presented the English-language translation of the book

Everyday Saints and its

author [Archimandrite Tikhon (Shevkunov) ‒ transl.]. Among the many

Russian exponents are the letters of Emperor Alexander II to Abraham

Lincoln, and the wonderful color photographic images of Russian

landscapes taken much later by Prokudin-Gorsky.

Fr. Victor and I made our way by car to the center of Washington,

DC. We immediately felt and succumbed to the beating of the

socio-political pulse of the American capital. Right before us, from

one of the official buildings toward another, streamed a column of

handicapped demonstrators: the wheelchair-bound, blind, lame,

accompanied by friends and assistance dogs, gradually, unhurriedly,

moving towards the legislative branch of the U.S. government. The

next day, the nation was to be hit by a government crisis, when a

conflict between the Democrats and Republicans sent federal workers

on an unplanned vacation. The free museums closed, disappointing

thousands of tourists.

"The headquarters of Voice of America is right next to the capital’s

museums, and my office windows looked out onto the Capitol

Building," explained Fr. Victor, pointing at a corner office on the

second floor of a building. "When I started working here in 1977, I

promised myself that every day during my lunch break I would visit a

museum and look at the exhibitions. But this was only a dream: all

my free time was devoted to parish matters."

"At First, I Was Only a Voice…"

"I

was first hired by Voice of America as a translator of news. There

was a radio and TV program led by Vladimir Matlin, a Jewish man, who

broadcast under the name of Martin. Once during a meeting, Volodya

said, to his credit: ‘Why am I running this show if we have a

priest?’ So they gave me twenty minutes before the Jewish segment,

then we made an agreement with Volodya that we would divide the

broadcast in half. The question arose about how to present me, since

it was unprecedented for a priest to lead a VOA program. First I did

not identify myself. At first, I was only a voice. Debate continued

for a while. As we discussed how I should be introduced, I created a

special program called ‘The Meaning and Structure of Nativity

Services.’ This was a purely Orthodox Christian broadcast, with

singing and Gospel readings. Suddenly, from Cavendish, VT, where

Alexander Solzhenitsyn lived, the head of the Russian Department,

Victor Frantsuzov, got a phone call; it was from Natalia

Solzhenitsyn, who said that Alexander Isaevich was impressed by this

and other religious programming and wondered who was responsible for

them. Management was flattered, and cooler heads prevailed: Why be

coy about this, it’s a priest ‒ he is an authority! So, six months

after starting at VOA, I began to open my broadcasts with the words

‘Priest Victor Potapov at the microphone.’ We begin our weekly

broadcast of Voice of America’s Overview of Religious-Social Life.

Then as I signed off, Volodya Matlin would begin his segment. I was

later given more time, and I was given a new slot called ‘Religion

in Our Lives.’ We separated from the Jewish segment, and my portion

lasted 45 minutes and was aired five times a week. I also arranged

for a weekly broadcast of Liturgy from St. John the Baptist

Cathedral, with a sermon; meanwhile, on a daily basis, after the

political segment and news, an excerpt from Holy Scripture was read.

In the 1990’s, I began to record two weekly segments of ‘Religion in

Our Lives,’ which would air several times."

"I

was first hired by Voice of America as a translator of news. There

was a radio and TV program led by Vladimir Matlin, a Jewish man, who

broadcast under the name of Martin. Once during a meeting, Volodya

said, to his credit: ‘Why am I running this show if we have a

priest?’ So they gave me twenty minutes before the Jewish segment,

then we made an agreement with Volodya that we would divide the

broadcast in half. The question arose about how to present me, since

it was unprecedented for a priest to lead a VOA program. First I did

not identify myself. At first, I was only a voice. Debate continued

for a while. As we discussed how I should be introduced, I created a

special program called ‘The Meaning and Structure of Nativity

Services.’ This was a purely Orthodox Christian broadcast, with

singing and Gospel readings. Suddenly, from Cavendish, VT, where

Alexander Solzhenitsyn lived, the head of the Russian Department,

Victor Frantsuzov, got a phone call; it was from Natalia

Solzhenitsyn, who said that Alexander Isaevich was impressed by this

and other religious programming and wondered who was responsible for

them. Management was flattered, and cooler heads prevailed: Why be

coy about this, it’s a priest ‒ he is an authority! So, six months

after starting at VOA, I began to open my broadcasts with the words

‘Priest Victor Potapov at the microphone.’ We begin our weekly

broadcast of Voice of America’s Overview of Religious-Social Life.

Then as I signed off, Volodya Matlin would begin his segment. I was

later given more time, and I was given a new slot called ‘Religion

in Our Lives.’ We separated from the Jewish segment, and my portion

lasted 45 minutes and was aired five times a week. I also arranged

for a weekly broadcast of Liturgy from St. John the Baptist

Cathedral, with a sermon; meanwhile, on a daily basis, after the

political segment and news, an excerpt from Holy Scripture was read.

In the 1990’s, I began to record two weekly segments of ‘Religion in

Our Lives,’ which would air several times."

"The Mudslinger"

"Voice

of America’s broadcasts were often jammed. It was so painful; you

put in so much work, your heart and soul… In 1984, I was sent to

Russia for the first time. We had a program wherein all employees

who had never been to the country they reported on had to travel

there for 2-3 weeks, to get to know the situation, ‘breathe the

air’… By then I had already worked at the station for seven years, I

had name recognition, and I was given a diplomatic passport, for my

protection. Just before my trip to Moscow, the periodical ‘Trud’

published an article called ‘Mudslinger,’ in which Soviet citizens

were warned not to meet with me.

"Voice

of America’s broadcasts were often jammed. It was so painful; you

put in so much work, your heart and soul… In 1984, I was sent to

Russia for the first time. We had a program wherein all employees

who had never been to the country they reported on had to travel

there for 2-3 weeks, to get to know the situation, ‘breathe the

air’… By then I had already worked at the station for seven years, I

had name recognition, and I was given a diplomatic passport, for my

protection. Just before my trip to Moscow, the periodical ‘Trud’

published an article called ‘Mudslinger,’ in which Soviet citizens

were warned not to meet with me.

"I took a receiver with me, and after settling in to the Ukraina

Hotel, tried to tune in to my own broadcast, to see how it sounds

there. All I heard was a horrible noise! My friends consoled me,

saying that local Russians attach antennas, put the receivers on

window sills, on radiators; in a word, they made adjustments and

listened. Later, when Gorbachev declared the policies of glasnost

and perestroika, letters from all over Russia came pouring in. Many

of them were addressed to me personally. Some I answered on the air,

and I have kept all of them to this day for future scholars of

Russian-American relations in the late twentieth century.

"Our parish set up a fund called ‘Spiritual Literature for Russia,’

and Voice of America would cover the cost of sending packages to our

listeners. It was an exciting time!

"Thanks to VOA, I met many fascinating people. Three times I visited

Solzhenitsyn in Vermont, I spoke to his wife Natalia on the phone

all the time. The third time I visited Solzhenitsyn was with

Vladimir Soloukhin in 1985. This conspiratorial visit was

unforgettable, and deserves special attention. At that time I became

acquainted with the scholar Dmitry Likhachev and many other

remarkable individuals. Alexander Ginsburg, the human-rights

champion, lived in our house six years after being released from

prison camp.

"My arrival at VOA coincided with the appointment of the virtuoso

cellist Mstislav Rostropovich as the Musical Director of the

National Symphony Orchestra. One of my parishioners, Nadezhda

Efremov, was his personal secretary and asked my matushka to be

Mstislav Leopoldovich’s interpreter, who was inviting French

composers to visit him. Over the course of 17 years, while he worked

in Washington, our families became very close, and Mstislav

Leopoldovich became the godfather of our daughter Sonya, and my

matushka and I became the godparents of his eldest grandson Ivan.

While our church was under reconstruction, from 1978-1982, Slava, as

we lovingly called the great Rostropovich, took an avid interest, as

he loved all kinds of construction. He was happy that the U.S.

capital was going to be the home of a grand cathedral in the ancient

Russian style, and helped build it. Every time Slava would visit

Washington, he rushed to see our church to evaluate the construction

process. He loved to climb up the scaffolding into the nave, and was

impressed by the craft of our architect, Bishop Daniel (Alexandrov),

and found much in common with him not only in architecture but in

music, literature and humor. Slava and his wife, Galina Vishnevsky,

the eminent opera singer who sacrificed her career helping

Solzhenitsyn, gave our cathedral a gift of five bells. The largest

bell has the names of seven great exiled Russian composers engraved

on it."

Under Republican President Ronal Reagan, Fr. Victor served as his

consultant on religious affairs in Russia. Soon after Fr. Victor

arrived in Washington, Fr. Alexander Kiselev gave him the

chairmanship of the Committee for the Defense of Persecuted Orthodox

Christians, through which Fr. Victor published the English-language

quarterly ‘The Orthodox Monitor,’ devoted to the plight of

Christians in Eastern Europe and the USSR. He managed to do all this

even while continuing as a parish priest and building the church,

one of the most beautiful ones on the East Coast.

Over the course of 35 years, Fr. Victor has been rector of St. John

the Baptist Cathedral, and several generations of parishioners have

passed through, recently complemented by new immigrants. Life in the

capital has left its mark on the church’s daily life: many

parishioners are scholars, artists, graduate and post-graduate

students. There are also many American converts; so many, in fact,

that every Saturday there are two Vigils ‒ first in English, then in

Slavonic, and two Sunday Liturgies. Five priests and four deacons

conduct the services.

And what about the founders of the parish? We round the corner of

Shepherd Street and head for the oldest cemetery in Washington.

First it was for Protestants and Catholics. In the early 1960’s, St.

John the Baptist Parish acquired a large parcel for burying its

dead, and ten years ago, a chapel was built, like a Fabergé egg,

consecrated by Metropolitan Laurus in honor of the Iveron Icon of

the Mother of God of Montreal. The altar table is made of Jerusalem

stone. Inside is a depiction of St. John of Shanghai, the parish’s

founder, and Jose Muñoz-Cortes, the murdered guardian of the

myrrh-streaming Iveron Icon of the Mother of God of Montreal, who is

particularly revered by the Potapov family. They are still in

possession of the personal effects of Brother Jose until a museum is

established in his honor. On Soul Saturday, commemorative Liturgies

and panihidas are served here, and the graves of reposed Orthodox

Christians are visited.

Buried here is a benefactor of the parish, a highly-ranked officer

in Vlasov’s army, Dmitry Levitsky, who lived to one hundred years of

age. Ivan Sivy is remembered not for his rank, but for his zealous

service to God. The old Carpatho-Russian died right in church after

Liturgy, before the commemorative table in front of the large

Crucifix. Konstantin Boldyrev is buried here, an active member of

the National Labor Union (NTS). In the 1940’s, Boldyrev was the head

of the DP camp where Fr. Victor was born.

Arkady

Shevchenko, former Deputy Secretary General of the United Nations,

buried here at the expense of the parish, was baptized, married, and

buried by Fr. Victor.

Arkady

Shevchenko, former Deputy Secretary General of the United Nations,

buried here at the expense of the parish, was baptized, married, and

buried by Fr. Victor.

The parish plans to erect a monument and bell in memory of the

victims of communism next to the late Soviet dissident Mikhail

Makarenko, who organized the first unofficial avant-garde art

exhibit in the USSR.

The Russian section of the cemetery includes the grave of the

renowned monarchist and journalist Yuri Meyer. His daughter, Natalia

Clarkson, was Fr. Victor’s superior at VOA. The Russian Department

there had some 120 employees.

The cemetery is also home to the remains of Tamara Stebletz and Olga

Rabchevsky. Elena Yakobson, a parishioner, was a professor at George

Washington University. Her voice was the first to be heard on the

VOA broadcasts to the USSR. Givi Kobi, renowned among the Orthodox

Christians of Washington for his generosity, former head of the

Georgian Department of the VOA, lies here, too, with his wife Maria.

Elena Fortunatova-Cox, Editor-in-Chief of one of the first glossy

magazines in the USSR, America, is here, too. Better known as

Lyalya, she was for a long time the choir director and secretary of

the parish council, and baked prosphoras. Her husband, Leonid Cox,

learned Russian and Church Slavonic, and read in church with an

expressive, southern accent.

"The kind souls of the founders of our parish’s benevolent fund,

which is active to this day, served as remarkable examples of the

Christian life," said Fr. Victor. "Our cemetery is home to many good

Russians who in the 1950s pooled their pennies, buying individual

bricks to build our wonderful church."

***

"Long before the events of 1991, I always told Russians that the

time will come when my broadcasts will end, because they will no

longer be needed, because such programs will be produced in Russia

itself, and they will be much better," continued Fr. Victor. "I

worked at VOA for thirty years, and I feel that I played a role in

the events of 1991. VOA is not the same today: once one of the most

renowned news sources in the world, it is now an informational

website. Our parish has grown since then anyway, and I could no

longer continue to occupy myself both with journalism and being

parish rector. Over 36 years in Washington, DC, I have met with many

remarkable people, thousands of hours on the air and the joy of

communicating with my listeners in the Soviet Union and Russia. I

fulfilled my role as a journalist and I am eternally thankful to the

Lord for the opportunity to partake in the religious rebirth of my

fervently-beloved historic homeland."

Tatiana Veselkina